Swept Under the Rug: Solving San Diego’s Homeless Issue isn’t as Easy as it Seems

May 14, 2014

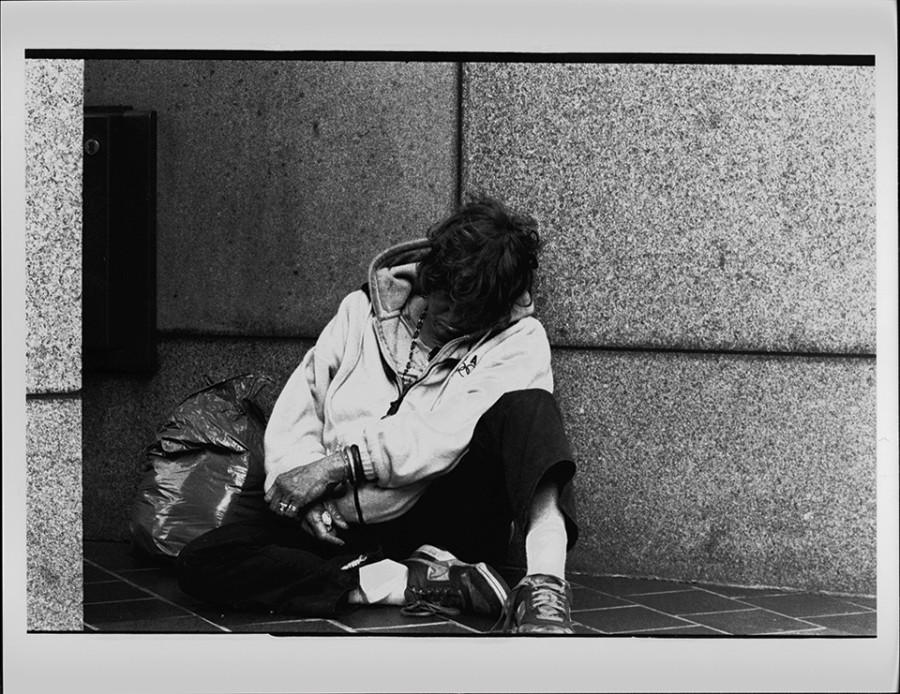

They’re all around us, you’ll notice. Take a stroll after class and you’ll see them surrounding San Diego City College. Try to walk to Pokez for a bite to eat and their blue tarp and shopping-cart-made homes are what you pass along the way. Even when you try to catch a trolley, you’ll find them lingering at the nearby station, asking for quarters, selling cigarettes and hanging out across the street. They’re San Diego’s tired, poor and hungry. The people swept under the rug of America’s finest city — the homeless.

In 2012, before he left under a cloud of scandal, Mayor Bob Filner promised that San Diego would finally be the city that would end homelessness. In the two years since that promise was made, the residents of this city haven’t exactly been marveling over the steady improvements. What with the homeless population going down from the 8,879 reported in 2013 to the 8,506 in 2014 as reported by the Regional Task Force on the Homeless. Yet strangely, there seem to be new crops of homeless people appearing in the city.

Those dirty faces familiar to San Diego have heard odd legal terms such as “illegal lodging” and seen shiny new signs encoded in difficult-to-translate ordinance numbers, designed to make the weary decide whether to risk trying to sleep near the Civic Center.

Compassion and patience begin to wear razor thin. Police and business owners in the heart of downtown where the homeless once primarily accumulated have started enforcing laws against loitering, trespassing and, yes, illegal lodging. The homeless community still ends up having to frequent the area, as their Social Security, disability, veteran’s checks and other benefits offices are available in that central area.

Temporary housing is usually on shaky ground as each shelter operating in San Diego faces three common worries: How long is the shelter going to be open? Are there going to be people who have to be turned away? Can funding sustain it?

With those stresses in mind, shelters are forced to do what they must. Single able-bodied men are least likely to receive housing in a shelter when single families and the elderly in need of dire medical care show up.

Police have been given legal permission to ticket homeless people sleeping in city corners and in dirty doorways in violation of “illegal lodging,” as if they are unwanted vegetables on a plate. The piles of San Diego’s unwanted have been pushed around to its outer edges. They’ve been shuffled to Imperial Avenue, East Village and, of course, the streets around City College, until the city can declare it’s done.

And that’s been the repeating pattern seen in efforts to end homelessness here. It’s been a game of red light, green light. Regardless of whose administration was in charge at the time, whether if the effort put forth was little or mishandled, those efforts eventually stop cold and the city is at a standstill.

Considering that in 2013, San Diego ranked 16th for homeless funding by the same report mentioned above, why would this city still attract any transient to stay here? The homeless issue is complex, one that is both social and economic. It could spark a 10-hour conversation on either side.

The answer is simple enough to grasp.

It was once said in a folk song that “California is a Garden of Eden, a paradise to live in or see. But believe it or not, you won’t find it so hot if you ain’t got the do-re-mi.”

While waiting in a long line to receive a meal from the Serving the Hungry volunteers, wily East Coast native John touches upon that sentiment, saying in an upstate New York accent, “Well let me tell you it’s the weather. In the east you freeze. I’ve stayed in Florida and the rays cooked me, no matter how strong the pH in my sunscreen was … here though, it’s nice even at night.”

It makes perfect sense when you think about it. It explains why San Diego now holds the No. 4 spot of the highest homeless population in the country, numbers according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The college students who pass these dirty faces walking to and from classes may actually share many commonalities with these transients. Though on different planes of struggle, there is an innate bond between the two. Both carry on in a world they’re not entirely sure of. Both are resourceful and have their own reasons for being where they ended up in the present. And how could anyone know of the radical changes that were to come when they were young? There isn’t any need to walk farther into downtown to learn that. Right now, there are peers in this school, sitting right next to you in classes, who are living this reality.

“The economy slump really changed people’s perspective of the homeless,” says Benny McFadden, a former City College student who left his productive academic run to find work and stability after handling back-to-back semesters without a home. “January of 2009, I started at City College as a RTVC (Radio, Television, Video and Communications) student. Previous to that, since May of 2007, I had been either unemployed or only able to find part-time work. And my financial situation became so severe, I was living in my car the full-time when I was attending the college.”

McFadden toughed out those times living in his car, where he spent the first couple of nights sleeping with a tire iron and a blue industrial flashlight in his hands. He collected cans and bottles to afford the gas going into his car and made the best of that basic Cal Grant, which to his great relief, he learned he qualified for. He waited in lines of irate people yelling claims about line cutting for seven hours to get food stamps, only to be told to come back tomorrow and start right over again.

For McFadden, school gave him much-needed stability.

“Attending City did not end my homelessness immediately but it did force me into a set schedule of activity much like working full time, that gave me a centered feeling of stability that I had not felt for a long time before that,” he said.

McFadden waited in the parking lot at Ninth and Union streets, where Serving the Hungry volunteers gather to hand out free meals. Homeless natives in the know of the group have dubbed them “The Chicken People.”

The homeless there wait up against fences and huddled in corners, conversing among their collective as conversation is the only means to pass time. This line is nearly identical to the food line seen by the Salvation Army two blocks away on most weekday afternoons.

The Chicken People gather their supplies into the back of one red truck bed. Half of them fix the night’s meal. They serve bread rolls, water bottles, graham crackers, bagels, chips and, yes, fried chicken, too. The rest of the volunteers pass the word along to those waiting, and plan ways of serving and ways to let more people find The Chicken People’s new location.

The Chicken People have served free meals under the Union and B Street overpass for the past five years. They are operating their charity in a parking lot today, and not that overpass by the jail as they have been doing for years, for two reasons.

First, the new courthouse that is being built next to the overpass and its construction is subsequently blocking the area.

The other reason is something on the minds of all the volunteers there that day.

Though never bothered, hassled or cited for the violation, The Chicken People were recently informed by the police that it is now illegal to give out food to the homeless here in San Diego County, as it is could be seen as an attempt to distribute poison.

They are very much aware of the possible risk and have made a choice.

Following the teaching of the carpenter son, they remain to serve food, as they have been doing every Wednesday for the past five years. They do it with attention to every detail. The food is handed out one item at a time, until it’s all distributed evenly per plate. A volunteer gives away a sweater to the one person who needs it. One woman takes laps around the line to pick up any trash left behind to help appease any residents who may complain that these lines ruin the neighborhood’s image.

The Chicken People do what they can.

Once they have finished serving the crowd at Union and B, they take to the surrounding areas in case anyone was missed.

“We’ll walk till we run out,” says Big John of the group. And they do. They find 12 more people, and along the way, stumble upon new parking lots where they can legally give food.

Some folks around the county may see homelessness as a primary excuse not to visit downtown. Tourists expecting America’s Finest City may be confused and annoyed to see poverty in abundance on their vacation. Is there any wonder why a person could become livid at acts of charity, like those similar to the ones that The Chicken People offer? Critics could venture to say that it may just attract more homeless people and danger, and encourage San Diego’s “they’re kind to homeless” reputation. It’s a stigma that remains and has been placed on all of those in the homeless community, and those homeless who don’t harm and are sound of mind have one more reason not to hold their heads high with that over their heads.

Whatever happens, once it all plays out and that red light is called, the people with their ear to the ground in San Diego are going to be the ones who have to pick up those fallen pieces. There will be more times to ignore the signs, the ones that say “Need money for food” with a wish for God to bless you, or ones that simply say “Hungry,” signs that try to affirm a worth they may have once had like “Veteran of foreign war needs to eat,” and even the more vulgar and honest ones like “Need money for weed and wild women … At least I ain’t bullshitting.”

There will be more shopping-cart-homes and luggage on the sidewalks to be seen, and more hearts will sink seeing a person curled in a thin blanket on the sidewalk in the dead of night.

There will also be hopes and good things to see, like acts of charity as big as The Chicken People or as small as a hug given to men who can’t walk, and the poor musicians who perform for their meals on Fifth Avenue and are simultaneously able to bring culture and a true metropolitan feel to San Diego as best as they can. There will still be homeless students sitting among us in our classes, unbeknownst to everyone else.

Whichever way the homeless problem sways or stalls, we’re going to have to take it all in day to day.

wellnow • May 14, 2014 at 10:29 pm

This article omits the Huff militant homeless group for some reason. It also neglects the expansion Father Joe always does with his homeless group, as well as the SD Rescue Mission’s expansion into the wealthier realms of San Diego.

What to do with the homeless? Keep them from mobilizing, maybe. That just brings more attention to them, and makes it more profitable for those persons unethical enough to make money on the destitute.

Why doesn’t Tiny Tim get his turkey? Because Barny had his doors closed on him by Mayor Golding when she did her downtown beautification project and closed Barny’s Liquors, the Monte Carlo and St. Pauli hotels, Henry’s B-B-Que, and who knows what else when the urban blight brigade got started. All the homeless lost their payees then, but they still abound.

Missed that part of the article, where is it?

August • May 14, 2014 at 7:21 pm

I hope San Diego likes these fires; what did the people of San Diego expect when they made being homeless downtown illegal and forced all the homeless into the brush?

CAMPFIRES NIGHTLY…..ENJOY!

mark marasso • May 14, 2014 at 4:37 pm

father joe puts ads in other cities on bus benches. “come to san diego we’ll take care of you”. no wonder there are so many, go out and ask the homeless where they are from. at least half are from other parts of the country.