Chinese women with 3-inch feet; a Japanese man adorned head to toe with tattoos and a Ubangi woman with lips protruding past the nose line. These were the first images shown to the spectators in San Diego City College’s room MS-162 on Sept. 24.

“I love this mural. It’s on display at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. It is by Alton S. Tobey,” Tori Randall said. “He’s basically showing a bunch of different ways of modifying your body.”

The “Cultural Mutilations in the Pursuit of Beauty” montage has been on display since 1966, but the body modification process has been around since long before that.

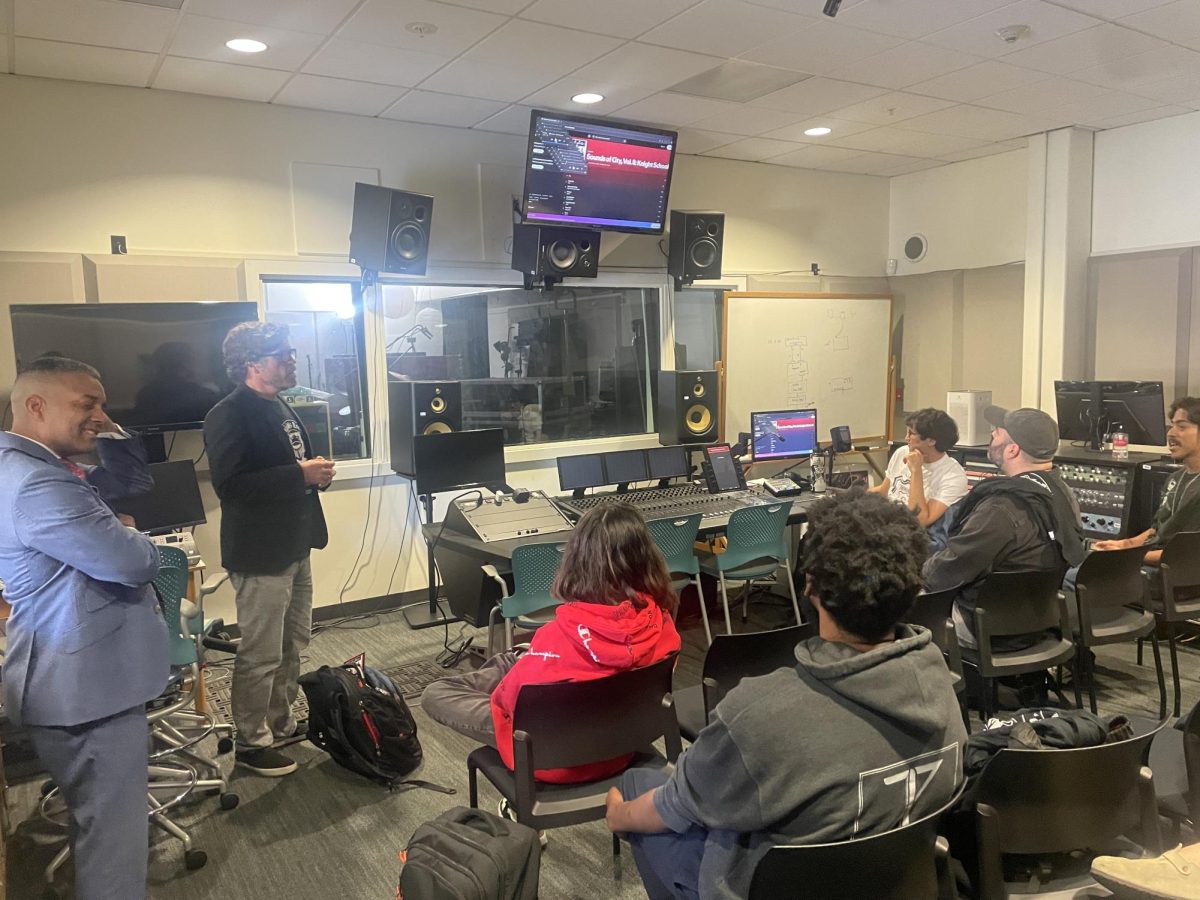

Randall, an instructor at City College with a Ph.D in biological anthropology, broke down the history of tattoos and a variety of other body ornamentation to the standing room only crowd.

“All populations use ornamentation in some way,” Randall said as she showed various photos from around the world on the large screen. “There may be multiple meanings and reasons for ornamentation and the actual ornaments themselves may have different meanings.”

Randall listed the different types of body ornamentation as being body painting, piercing, scarification, skeletal modification and tattooing.

Body painting is the most common form of ornamentation, with the application of make-up to one’s face or body for aesthetic appeal, or to cover parts one would want to hide, like a scar. Randall showed different cultures applying face paint, long before the likes of Maybelline and CoverGirl. The Seri indigenous men and women from Mexico paint their faces white for beautification purposes and the Mohave indigenous people painted the face of their girls as a puberty ritual when the girl was coming of age.

Piercing body parts such as the navel, labret, lips, nose and nipple, didn’t become mainstream in the U.S. until the 1990s, but the piercing of various body sites has been practiced for thousands of years.

“Piercing is when ornaments are inserted through body parts and the skin heals around the opening,” Randall said.

Randall defined scarification as “(when) the skin is cut and substances such as clay or ash are inserted into the wounds resulting in permanently raised scars or bumps.” In Tanzania, the Hadza, who are one of the remaining hunters and gatherers left on this Earth, practice scarification as puberty rituals.

“This young boy is getting his back scarred, (where) they are making the incisions where it will scar over,” Randall demonstrated by showing the closeup of an elder holding a small tool by the kid’s lower back.

Showing another example of scarification, Randall said: “This little girl is celebrating with those two scars on her cheeks is celebrating that she has gotten her period and is now a woman.”

Skeletal modification is the “alteration of bone to change the shape of the body.” A photo of a corset was shown, then next to that was a drawing of before and after skeletons.

“Back in the 1800s, where the corsets were cinched super tight, the idea was that they looked prettier with a slimmer waist,” Randall said, as she directed the attention to the ribs area of the skeletal portrait on screen. “This is someone that’s been wearing a corset, and has had her ribs continuously broken in order to wear this corset all the time … and when they heal, they heal in the smaller shape.”

Randall explained that people get tattoos for five different reasons: aesthetic, rites of passage, group identity, self expression, and ritualistic.

“I got my first tattoo yesterday and it was a super cool and fun experience. However, it did hurt,” Randall said as she pulled up her sleeve, “I got a sugar skull because I’m a physical anthropologist, but I’m also very colorful in my life.”

Various methods of applying ink into the skin were also explained, and demonstrated via video; from the early style of hand-tapping in Polynesia, to the machines originally made in England.

“(Body modification is) a really cool anthropological concept and I think it really resonates with our students here at City,” Randall said.