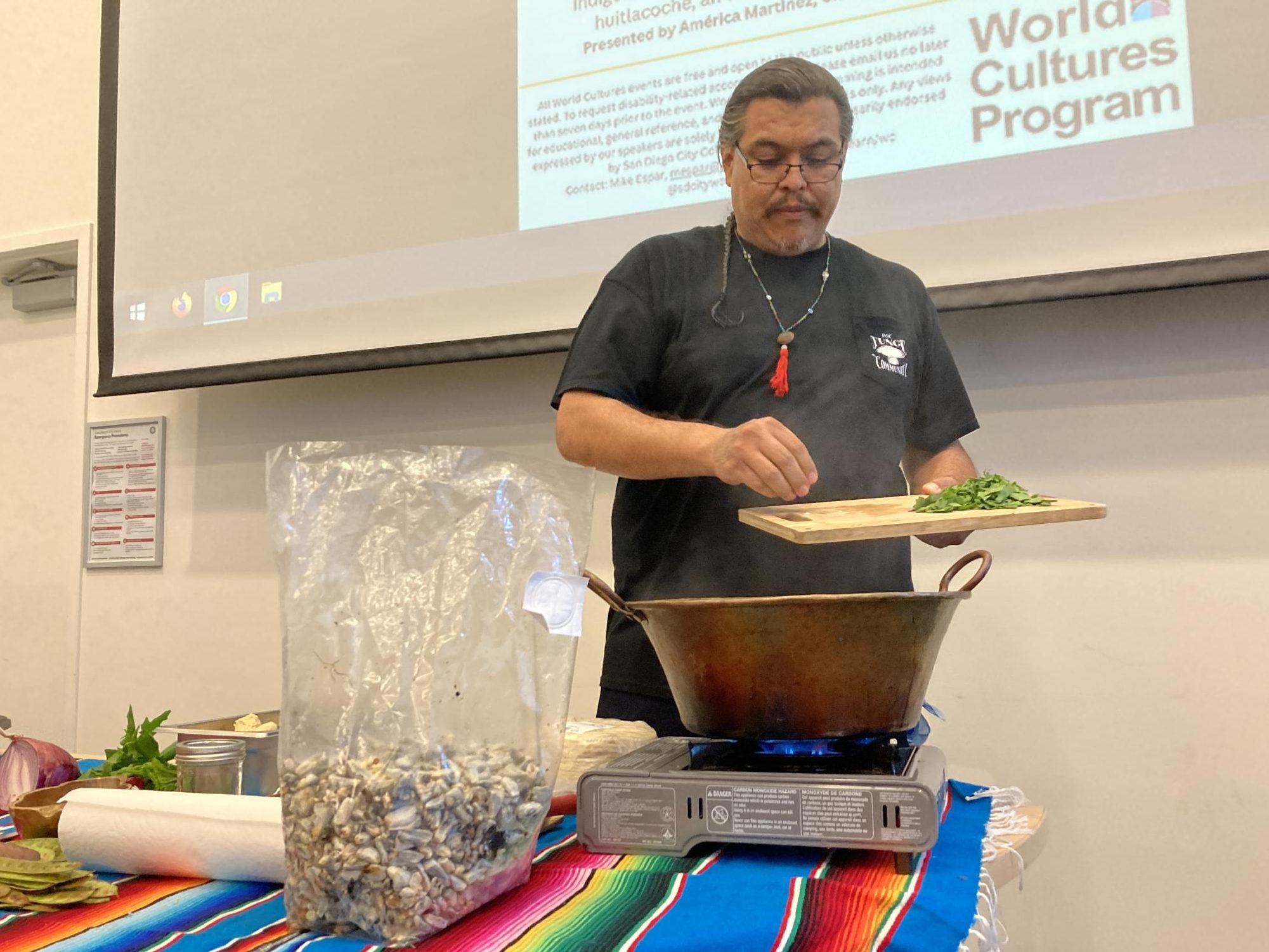

Three San Diego City College students worked around a brightly colored Mexican blanket-covered table topped with a bronze cazo, an assortment of traditional Mexican ingredients and a large bag full of an earthy-looking substance: huitlacoche.

Each student had a designated role: one made tortillas from masa, another shredded cheese for quesadillas and the third transported the freshly made tortillas from a comal to a tortillero.

Roughly 90 students filled the meeting room to attend “Indigenous Food Sovereignty: Discussion & Food Demonstration with Huitlacoche,” as part of City College’s World Cultures fall calendar.

Some attendees stood against walls and by doors, pushing the boundaries of the demonstration space’s capacity.

America Martinez, event organizer and professor in the Chicana/o Studies department, greeted attendees in room MS-140 while introducing Mario Ceballos, POC Fungi Community presenter of the Oct. 18 food sovereignty discussion.

“One of the reasons we put this together is because it’s so important to connect to our raíces to our cultura and to maintain those connections,” Martinez said. “That’s the heart of this event.”

Huitlacoche, whose name is rooted in the Nahuatl language, is an edible fungus in Mexican cuisine that grows exclusively on corn. The English word for it is “corn smut.”

“To indigenous people in Mexico and all over Turtle Island (an indigenous name for North America), it’s traditional food, it’s a delicacy, to some it’s medicine,” Ceballos said. “Some indigenous folks don’t eat it but they revere it and it’s part of their creation story.”

The corn fungus is a nutrient-dense food with antioxidant, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

It’s a whole source meal that contains lysine, which is normally found in poultry, fish, cheese, or eggs, according to Ceballos.

For a vegan or someone that doesn’t have access to meat, huitlacoche provides a full diet and complete source of nutrition, Ceballos said.

The mycology proponent, who is also co-chair of the Yaquis of Southern California, said that due to indigenous people’s diet consisting of amaranth, crickets and similarly nutritious foods, settlers and colonizers saw native people well into their old age climbing mountains and doing work with abundant energy.

The YSC co-chair said those traditional foods are now being commodified to make them more palatable for western culture.

“One of the names that (western culinary professionals) are using is corn caviar or corn truffle,” Ceballos said. “Somebody like me who’s involved in the food justice system and who’s trying to reclaim our food, I hear that and I cringe.”

Ceballos’ work, as with the theme of the presentation, revolves around food sovereignty, the idea that having access to healthy food is a human right and an integral component of social justice.

“Food sovereignty to me means medicine and food for all, access to our ancestral foods without restriction, without having to go through Customs and Border and claim that I have huitlacoche and risk it being taken away,” said Ceballos, who is of Yoeme descent.

If someone in the U.S. would like to obtain huitlacoche, they have to travel into Mexico and bring it into the U.S., as Ceballos did for the presentation.

It is not illegal, he said, but it is frowned upon.

According to the National Institute of Health, huitlacoche is seen as a phytopathogen, or a plague.

Travel into Mexico is not accessible to all people whose ancestors once thrived with diets consisting of nutrient dense foods such as amaranth, chia, and huitlacoche, Ceballos added.

“To me,” Ceballos said, “the only reason we need food sovereignty is because borders exist.”

Diana Goss, a student in Martinez’s Chicano Studies class, attended the event to earn extra credit.

Learning about ancestral foods such as huitlacoche sparked something in her.

“It honestly makes me want to change my major,” Goss said. “I’m Mexican American and I’ve just been living this American life, so now I’ve become a lot more passionate about my roots.”

“I feel this energy coming out of me where I want to change other people’s minds and make a movement, but I just don’t know where to start,” said the 25 year-old nursing major.

Before continuing with the discussion, Ceballos played a short film, “Flor de Maiz,”by Magdalena Ramirez. The roughly 10-minute documentary elaborated on the cultural impact of huitlacoche in the San Diego Latinx community and some of the work done by the POC Fungi Community.

When the lights came back on, Ceballos walked around the room with a 2.2 pound bag of huitlacoche.

He handed students huitlacoche galls, infected corn kernels, to inspect, asking students to reflect on what they’ve been taught about mushrooms.

He recounted his own experience of being taught to fear mushrooms from his parents, highlighting the need to learn the beneficial properties of fungi.

As he prepared the food demonstration, he asked the audience to join him in taking a deep breath.

“We’re gonna ground, we’re going to kind of take note of your surroundings, of what you’re smelling,” Ceballos said. “To me that’s a form of resistance. That means that this food, this medicine, can’t be contained in here.”

For Goss, the invitation to ground and be present with her senses as the huitlacoche cooked offered a new framework with which to experience food.

“I’m feeling passion towards my culture and I feel like for the longest time, I’ve gotten rid of that passion,” Goss said. “I literally make chicken, rice and asparagus for dinner, but now I want to make huitlacoche and quesadillas and kind of go back into my roots a little bit more.”

Ceballos continued making quesadillas as most attendees made their way to the brightly colored table to taste the huitlacoche quesadillas.

The line quickly formed and ran from the front of the room, almost reaching the entrance on the other side of the classroom.

The smell of sauteed onion, garlic, epazote, and huitlacoche wafted throughout the room.

Martinez reflected on the presentation as she closed out the event.

“Food is medicine. Through food, (we are) building community. Through food, (we are) nurturing ourselves and our families, our comunidades,” Martinez said. “One thing I’m taking away is the importance of connecting to our raíces and food is a way to do that.”

City Times Editor-In-Chief Marco Guajardo contributed to this story.

Martha Guthrie • Oct 21, 2023 at 8:45 pm

“If someone in the U.S. would like to obtain huitlacoche, they have to travel into Mexico and bring it into the U.S., as Ceballos did for the presentation.”

I live in Dayton, Ohio and have gotten Huitlacoche from a farm market and from a friend with a cornfield.

It’s pretty easy to find on corn not treated with a fungicide.