Doug Porter has been telling San Diego’s story for over 50 years.

From his early years covering the anti-Vietnam War Movement to his commentary on the 2024 election, the writer and activist has worked to expose the dark side of a city that for many is a vacation destination.

“Doug’s history is kind of like a secret history of San Diego,” said Jim Miller, a City College professor and longtime collaborator of Porter’s. “It’s the San Diego tourists never see.”

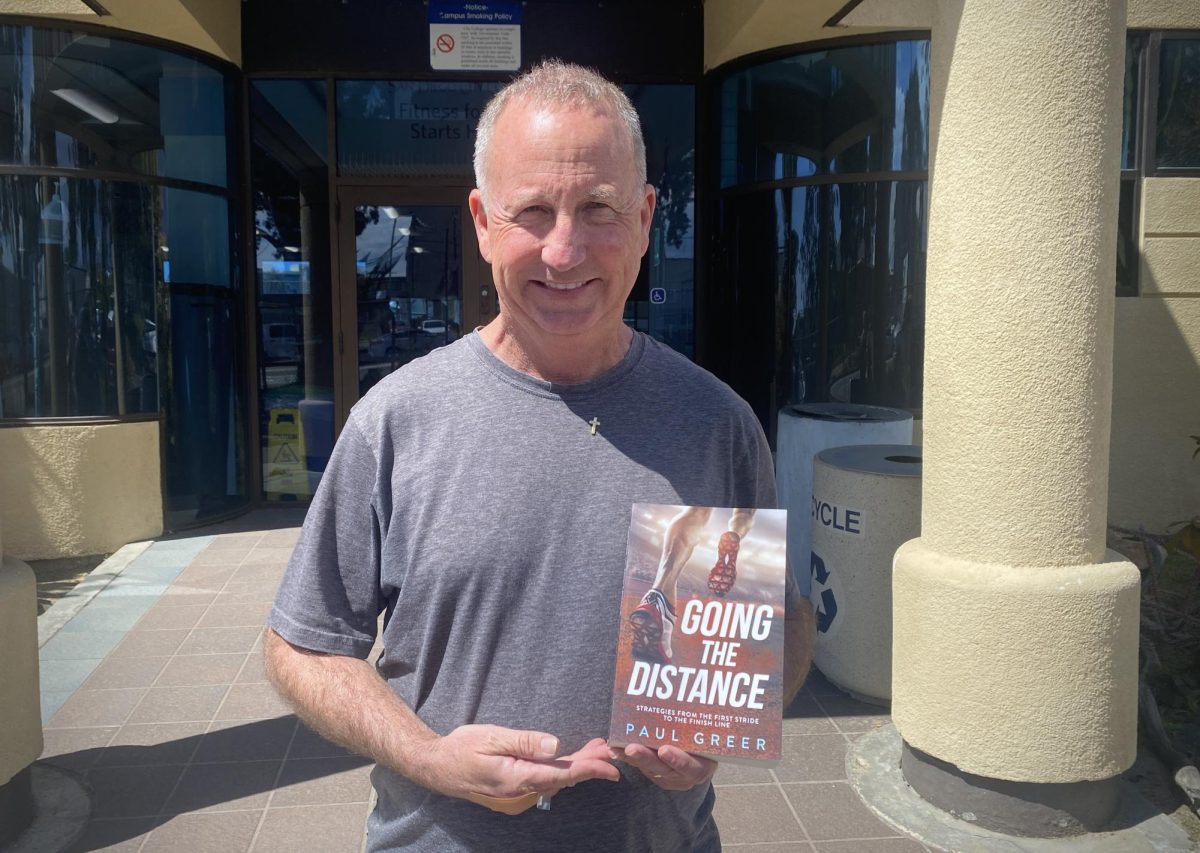

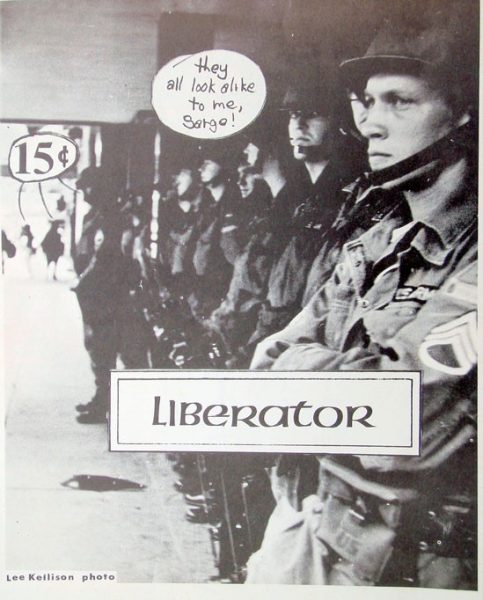

Porter got his start as a teenager documenting San Diego’s counterculture and the anti-Vietnam War movement while running The OB Liberator, an underground paper he started with friends.

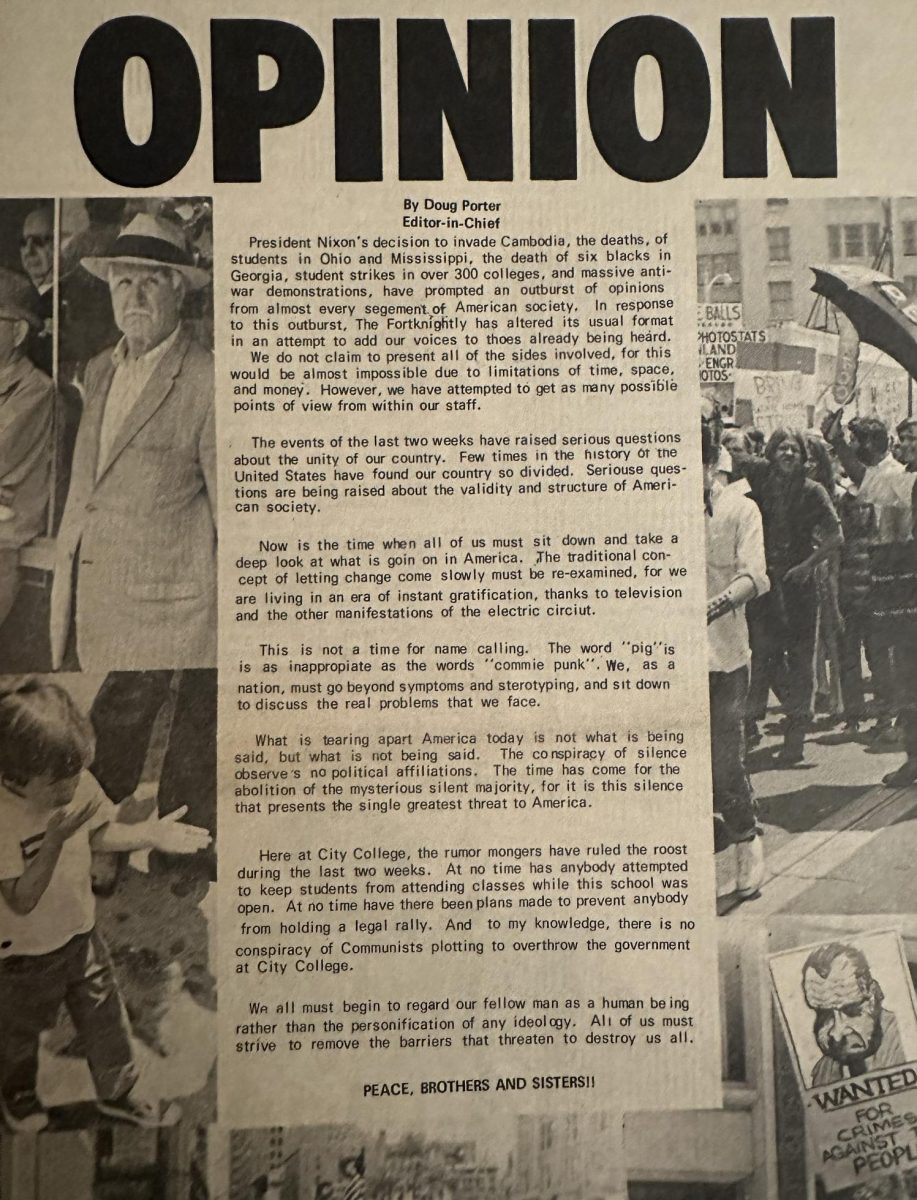

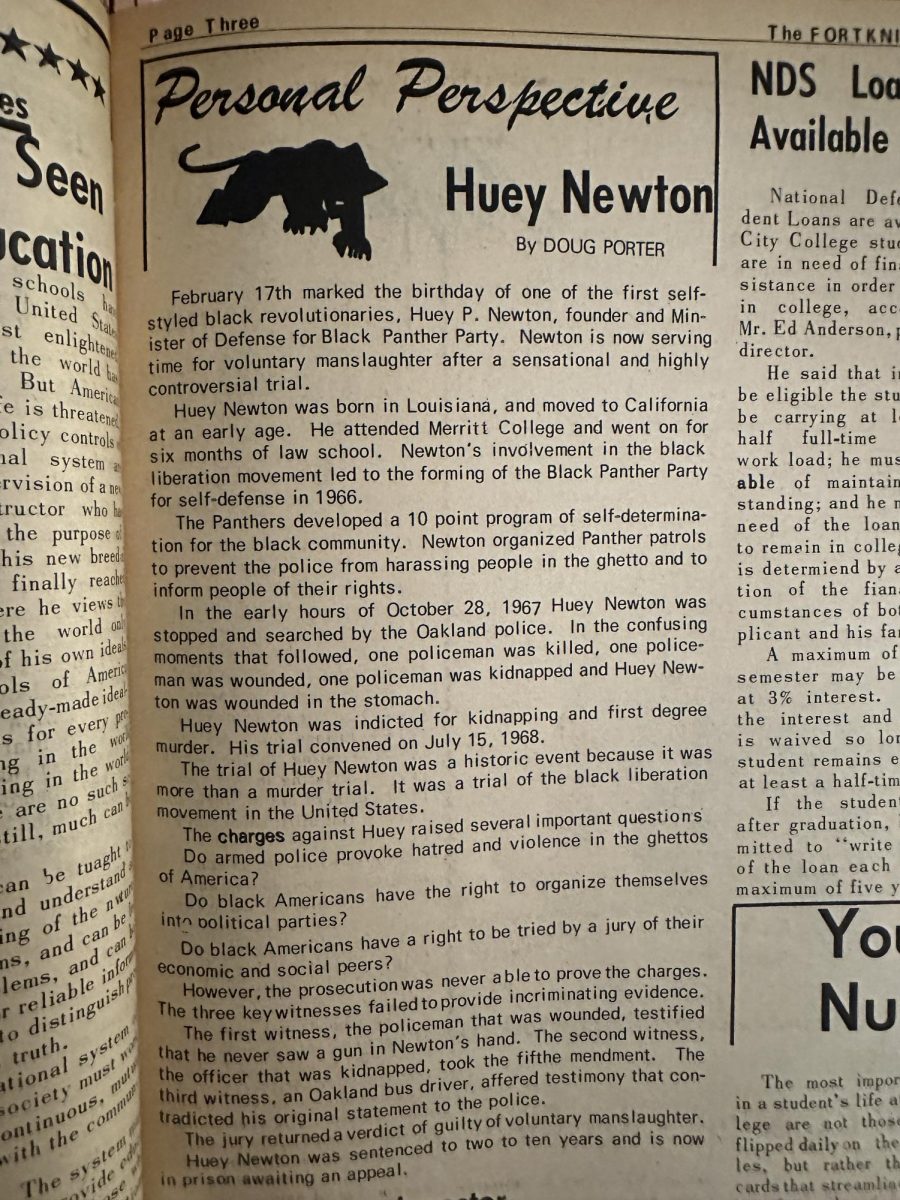

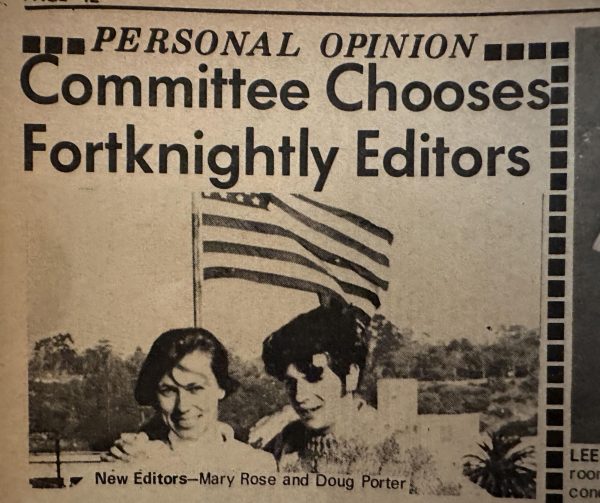

In 1968, Porter enrolled at City College and began writing for the Fortknightly, City College’s student newspaper which evolved into City Times. In 1970, he became co-editor and took the paper in a noticeably more political direction, covering topics such as civil rights, environmentalism and the wars in southeast Asia.

In the spring of 1970, he participated in the student strike against the U.S. invasion of Cambodia and never returned to school.

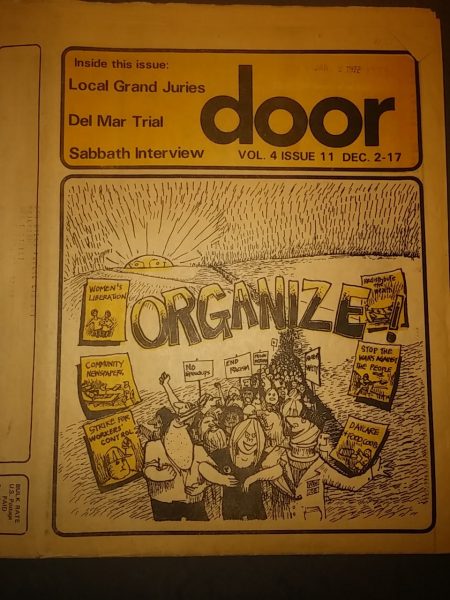

But Porter didn’t stop writing and fighting for progressive causes, eventually contributing to outlets including the OB Rag, The Door and CounterSpy.

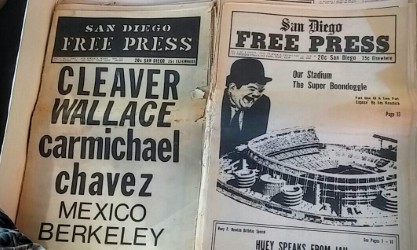

He says he was driven out of the movement and left activism for a number of years before returning in the 2000s to work at the revived OB Rag and the San Diego Free Press.

In 2021, the San Diego County Board of Supervisors announced that October 21 is Doug Porter Day and presented him with an award for his lifetime of work.

Today, Porter’s work can be found at Words and Deeds on Substack and Jumping-Off Place, a blog run by Miller and Professor Kelly Mayhew.

“He’s fearless,” Mayhew said. “He’s sharp and he’s really funny, but his fearlessness, I think, speaking truth to power, is what stands out to me.”

Porter was interviewed by City Times about getting started in journalism and his time at City College. To read more of Porter’s story, check out his blog and the numerous interviews he has done over the years.

A throat cancer survivor, Porter no longer has the use of his voice, so this interview was conducted over email. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.

City Times: What was San Diego like when you were in college? How has the city changed over the years?

Doug Porter: San Diego was a Navy town. Because enlisted sailors weren’t particularly well-paid, the downtown had a cheap feel to it. Lots of hole-in-the-wall places catering to (mainly) young men from rural places who were alienated, afraid and lonely.

I avoided downtown (except riding the bus through) once my hair started growing over my collar. A lot of the Navy guys were hostile towards those of us adopting various aspects of the hippie culture.

I was enrolled in journalism classes and, when we met a left-over beatnik looking to get into the underground press business, we agreed to join his effort. This was the OB Liberator.

Norman, who was stranger and a lot older than us, lived with his mother on Cape May Street. He had an offset printing press in his garage and had published some anti-war fliers advocating free-love as a way to change the world.

The first issue of the OB Liberator consisted mostly of clippings from other publications and hand-scrawled gibberish in the margins. My roomies sold that first issue at the foot of Newport Avenue for 15 cents. They got hassled by the cops a lot.

CT: How would you describe your experience at City?

DP: My experiences at City College were centered around Journalism 101/2 classmates. The war in Vietnam was always being discussed and argued about. Some classmates were pro-war veterans, so each day brought new tensions.

I was vaguely interested in my other classes, mostly those with faculty willing to engage in the issues of the day. I remember getting a grade lower than expected (I’d done the work) from a philosophy professor who perceived anti-war activism as an excuse to burn American flags.

In the Spring semester of 1970, I was named as co-editor of the Fortnightly. Much of our content was boosterish reporting on campus activities, so the editorial page was where the action was.

The faculty advisor for the paper thought he’d saddled me with a more conservative co-editor, not knowing that we were quietly double dating with two “older” women working for the main office of the college administration. I was getting high with my straight looking counterparts on the weekends, and all kinds of things “accidentally” made it into the paper.

We were using the paper’s darkroom to develop and print photos of undercover cops shadowing anti-war protests and passing the results on to a staff member at the San Diego Street Journal, a local lefty underground paper.

Everyday routines fell apart in May at the campus as schools nationwide shut down for anti-war protests. I and many others stopped going to classes but came to campus to debate the issues. There were anti-war rallies in the area outside the cafeteria.

Excitement was in the air – we thought our student movement was going to change the world. I started a daily “underground” 8-by-14(-inch) sheet, initially printed on a mimeograph machine near the college president’s office, thanks to our ‘friends’ in the administration.

When the strike fizzled out, I was told not to return to campus. I did somehow get passing grades for that semester

CT: Today, San Diego City College has a very politically active student body. What was campus like politically while you were here?

DP: It was pretty quiet, except for my last month there. Black and Brown students were the most active. Older students, mostly conservative white veterans, held sway on most school-sanctioned events and clubs. It was the Chicano students who got us all talking to each other in early May 1970 and it was (I think) the Black Student Union that got the U.S. flag lowered to half-mast.

I spent time hanging out at UCSD, where the graduate students were the most active, and began to read lefty literature.

CT: How do you think San Diego and City College shaped your politics?

DP: As a military brat who’d had to prove himself to yet another round of school bullies every couple of years, I’d never thought of myself as a leader until my second year, a role I assumed because of frustration with my classmates’ timidity.

Now I realize that many of my peers viewed City College as their best shot at having a better life than what they grew up in. I had the privilege of just being and not having to focus on my economic future.

I went on to assume leadership roles through the 1970s, as editor of the OB Rag, and then The San Diego Door. At one point I even co-hosted a weekend talk radio show (KSDO AM), safely separated from the rabid reactionaries who dominated the airwaves the rest of the time.

I learned my lessons about the pitfalls of leadership after I moved to (Washington) D.C. to become editor of CounterSpy magazine. I was, looking back at it, such an arrogant asshole. I was purged by the CounterSpy crew in 1976, after a (secret) member of the Revolutionary Communist Party claimed to have evidence I was working for law enforcement. I’d made the mistake of confiding to him that I thought overt revolutionists were fools, who’d be jailed when the opportunity arose.

One day I was a go-to activist, archivist and writer, able to cross lines between radical and liberal groups; the next, I was considered a traitor. I became unemployed, an unhoused couch surfer, and mostly friendless. I dropped out of politics and dropped into a destructive cycle of hospitality jobs, alcohol, and drugs. Somehow, I fooled a lot of people into thinking I was kinda “normal.”

CT: Last spring, students at colleges across the country, including City, protested the war in Gaza, leading to a lot of comparisons to the anti-Vietnam War movement. As someone who witnessed and participated in that movement, what parallels do you see?

DP: Protests against the Gaza War were, and are, a righteous movement, seeking to inject a moral stance into a geopolitical world that’s about as amoral as it gets.

I was gratified to see activists at many institutions who’d learned end-arounds of the repressive methods of the state. People knew their devices were a liability; that leadership was better as an ad hoc process, so the movement wasn’t always vulnerable to getting its heads chopped off.

Sadly, I think the powers that be have also learned from the past. Groups that leaned on the mass media were susceptible to smears and misinformation attacks. It didn’t matter at Columbia that outsiders weren’t part of campus activism; allegations of egregious acts on nearby streets by provocateurs were reported in the mainstream media as part of campus actions.

And the development of a right wing media ecosystem that transcended conventional roles and platforms meant that allegations aired by a podcaster in Boston could be talked about on the floor of the House of Representatives a few days later.

CT: What was it like writing for the Fortknightly (now City Times)? How did it compare to your work at the OB Liberator?

DP: I was a terrible typist, and getting 250 words out took me forever. As part of my coursework, I was required to write stories with a lede, a middle, and an “objective” conclusion. I had to write headlines that fit using the font sizes that were available on the typesetting equipment. The Fortknightly had an agreed-upon format focusing on words, sentences, and paragraphs. Learning to function within those limitations was – although I didn’t think so at the time– a valuable experience, one not found on textbook pages.

Ninety percent of what we published made it into print because somebody expected it to be done, regardless if it had any relevance to non-participants. Being “Fortknightly” meant that even our sports coverage was stale, stale, stale. And our faculty advisor was absolutely committed to being as vanilla as possible. Most of our feature pieces were like essays about the color gray.

Working on the Liberator meant no deadlines, no format beyond having an eye-catching and usually sarcastic cover page, and having to paste in clippings that the copy-camera might or might not see as a half-tone checkerboard. We typed a few paragraphs here and there, again mostly sarcastic commentary on the “straight” world. And there was a lot of space taken up with spontaneous scribbles or cartoons in magic marker.

What the OB Liberator did accomplish was to lay down a marker about the community being chock full of hopheads, radicals, and freethinkers. It’s an assumption by many outsiders that lasts to this day, even though it’s no longer true.

It took me a few years to become aware of the joy of the craft of writing, but the challenges of those experiences set me on the path I follow today.

CT: What did you learn from your time at the Fortknightly? How did it influence your career?

DP: I mostly learned that information can be used as power, and looked at real world publications with awe. A high point of my underground press years was being paid as a stringer for Newsweek, even though my contribution was entirely phone calls to the reporter assigned to the Southern California beat.

I learned about setting goals, even when they weren’t realistic or when others chose to ignore them; if I had a plan, things always turned out better.