Fine art graduate returns to City after 30 years motivated by personal tragedy to realize lifelong dream

Following in his late daughter’s footsteps in an attempt to heal, Nilo Ondevilla found human connection, mentorship and a future beyond his imagination

Nilo Ondevilla paints his work dedicated to the Philippine High school for the Arts. April 24, 2023. Photo by Kathryn Gray/City Times Media

May 25, 2023

Note to readers: This article discusses the topic of suicide. If you or someone you know may be struggling with suicidal thoughts, you can call or text the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or chat online any time of day or night.

Wearing a tan fedora, a black polo with a popped collar revealing big white letters that read Michael Kors, shining dog tags that drape around his neck, a charcoal pencil in one hand and a salted watermelon seed in the other, Nilo Ondevilla came to the studio with style and sustenance for hours-long marathons of creation.

With the fervor of a recent high school graduate, Ondevilla, 59, approached art and life with unrestrained ebullience. Graduating with an associate degree in fine art from San Diego City College in Spring 2023 and heading to the Art Institute of San Francisco in the fall – following stops for a summer leadership program at Yale and an art program in Florence, Italy – Ondevilla exemplified unwavering commitment to his craft.

A Navy veteran, a survivor of three suicide attempts and one stroke, with a hand and wrist ravaged after an angry punch to a concrete wall, Ondevilla never imagined he would be back at City College after almost 30 years away.

“I know there’s somebody watching and conspiring for my success,” Ondevilla said. “I’m trying to figure out why.”

It was a tragedy that brought Ondevilla back to City, but it was joy that made him stay. While explaining a drawing of a violin and a glass rhombus-shaped award given to his daughter Bernadette for choreographer of the year in 2013, Ondevilla said, “that is my joy.”

It was a knock on the door at 2:35 a.m. on September 6, 2014 when Ondevilla’s life changed forever.

“Bernadette celebrated her 23rd birthday, the last time I saw her happy,” Ondevilla said. “Six days later the cops came to my house and said to my wife, ‘she jumped the bridge.’ Her mom started screaming, her sisters started screaming, that scream of loss and pain. I woke up and I didn’t even have to say anything with that sound.”

When he saw the police at the door holding Bernadette’s YMCA uniform and other personal items, Ondevilla knew his beloved daughter would never walk through the door again.

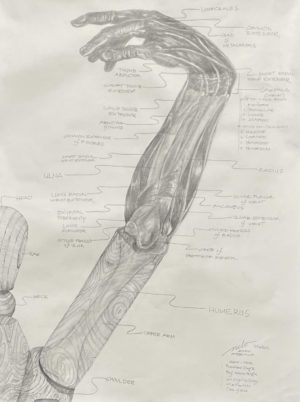

In a rage, he thrust his fist straight into the wall, smashing several bones and permanently disfiguring his wrist and right hand, an experience that inspired one of his works, which illustrates that part of his body.

“There were a few years there that I couldn’t grab a doorknob,” Ondevilla said. “It didn’t heal properly. I can’t do any push-ups.”

Ondevilla was shocked. He did not see any signs of Bernadette’s struggles.

Alicia Rincon, a UCSD dance professor and mentor to Bernadette, said she was blindsided as well when she learned such a driven, kind student and human being with a natural ability to connect with others had been suffering so deeply.

The experience has changed Rincon’s approach to teaching profoundly.

“I always keep an eye on people who seem to be struggling,” Rincon said. “I gently check in with students. In the world of dance, we bring everything we can. I encourage students to come to class and work through that pain and struggle.”

A UCSD graduate with a degree in psychology as well as an accomplished dancer and choreographer working with the City dance department, Ondevilla felt Bernadette was in a great place in life and facing only minor setbacks in the form of a breakup with a boyfriend and surviving a head-on car collision.

Ondevilla and his wife bought Bernadette a car in 2014 because they were so proud of everything she had accomplished. A few short weeks later, a head-on collision on Torrey Pines Road left the vehicle totaled and Bernadette shaken up by the experience. Referencing brain injuries of athletes like Junior Seau, Ondevilla suspects the impact of the airbag affected Bernadette in ways they couldn’t see.

“So in my mind, I still know that she just didn’t lose her mind,” Ondevilla said. “There’s a reason why, like a concussion, because, after the accident, her behavior changed.”

After losing Bernadette and prior to returning to City, Ondevilla spent five years living in a single room of his home consumed by suicidal depression, shutting out his wife, children and career.

His days, he said, were filled with sorrow, watching Netflix movies and opening his door when no one was around to grab the food and gifts his wife and other children would leave for him.

It was during this time that Ondevilla attempted suicide three times.

“I remember turning blue and as soon as I closed my eyes (during the last suicide attempt), I realized it wasn’t my last breath,” he said, “because I am supposed to be here.”

Ondevilla and his daughter Bernadette’s experiences are not isolated ones, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. From 2020 to 2021, suicide rates in the United States rose by 4%.

The increase in mental health struggles among Americans was most predominant among teenagers in 2021. A Center for Disease Control and Prevention report found 42% of high school students reported experiencing sadness and hopelessness on a long-term basis, a 14% increase since 2011. Among those surveyed, 18% made a suicide plan and 10% followed through with an attempt.

Teenagers who identified as female were especially vulnerable, according to the CDC, with 30% of those surveyed in 2021 reporting seriously considering suicide.

After five years of sadness and isolation, Ondevilla found a way to reconnect with the outside world and enrolled in classes at City to feel closer to Bernadette. He took dance and art with professors who had previously worked with her as a student and a choreographer.

He found love for life again through art, he said, which has been a throughline in his life.

As a young child in the Philippines, Ondevilla’s parents would find him staring at a wall or into space laughing and ask him what he was looking at.

“When I was younger I could actually project movies on a blank wall,” Ondevilla said. “When I was like six, seven years old, I would be laughing my ass off because I was watching my own movie.”

Not only imaginative, Ondevilla was also talented and driven at a young age. At 11 years old he was chosen to attend the Philippine High School for the Arts. While there, graduating at 18, Ondevilla studied with Filipino master artists and honed his creative skills.

Although an artist at heart, Ondevilla took a traditional path after high school graduation, joining the Navy in 1984, serving active duty for 21 years and earning his bachelor’s degree in the process.

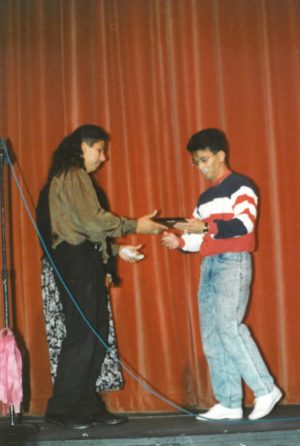

Ondevilla’s first experience at City was in 1993 when he was still on active duty and sent to study by the military. He made his mark the first time around as an Associated Students Government senator and then vice president, part of the team that advocated for permanently banning smoking in the cafeteria.

Ondevilla also realized that many of his fellow students did not understand Asian cultures very well. It prompted him to start the Asian Coalition to celebrate all of the Asian cultures represented at City.

“It’s not a melting pot, like what everybody thinks in America,” Ondevilla said. “It doesn’t melt into one piece, so you have the richness of different flavors of the different vegetables and meat of different cultures. So it’s not a melting pot. … It was a cultural bouillabaisse. Like a brilliant soup.”

Fellow ASG member John Gradilla, who held Bernadette as a baby and is now a City College counseling department staff member, remembered Ondevilla well.

“He was almost bigger than life,” Gradilla said. “Very happy, outgoing and always trying to get things done. For him, there was never enough time in the day to take care of all of the different things he wanted to do.”

Thirty years later, Ondevilla still had that drive. After graduating with his master’s from the Art Institute in San Francisco, he plans to return to San Diego, establish an art residency and use his entrepreneurship skills to provide for his family through art.

Advocacy was also top of mind for Ondevilla and he’s learned that a nuanced approach has been more effective than a brash one.

“I tried to barricade the Coronado Bridge until somebody spoke to me and said, ‘you realize you’re barking up the wrong tree,’” Ondevilla said. “‘Because even if you barricade that bridge, what are you gonna do next? Golden Gate? Washington State? Washington, D.C.? Montana? You’re going to barricade every bridge but there are still people that are going to die. Right?’”

Ondevilla took this to heart and refocused his efforts on educating others about suicide prevention.

“You know what the solution is? Education,” Ondevilla said.

A fierce advocate involved with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Ondevilla fought for the implementation of the National Suicide Prevention Hotline, 988.

Experiencing his own tragedy, Ondevilla said, opened his heart again not only to art but to other human beings in a way he hadn’t expected.

Ondevilla often visited friends from the Navy on Rosecrans Boulevard, where they now live unsheltered, exposed to the elements and often overlooked by society, he said.

With plans to create a program one day for veterans, starting with his seven friends living on Rosecrans Boulevard, Ondevilla hopes to train them with critical job and life skills.

Ondevilla said he wants to help others so they can continue to help themselves and compared his mission to the idea of “teaching a man to fish.”

“Maybe if I just start with those seven people, not 100,000 of them,” Ondevilla said, “I could get to those seven people and get them off the street.”

With the support of his family and professors, Ondevilla was ready to embrace the opportunities coming his way.

“Doors are opening up and I don’t understand why,” Ondevilla said. “They say God closes a door and then He opens another one or a window. Well, now He’s opened up a huge freaking gate. The things I don’t understand, I stop questioning.”

Fine Art professor Wayne Hulgin, who taught Ondevilla in the early 90s and is now one of his mentors, sees a future of success for Ondevilla.

“He’s just a natural drawing, you know,” Hulgin said. “He’s gonna have a great future because he’s so ambitious.”

Hulgin sees Ondevilla becoming a full-time painter or a teacher because he understands art and the business of it.

“He’ll be a good self-promoter, which it takes,” Hulgin said. “He can sell himself and that’s what it’s going to take and he’s the best person to do that.”

Hulgin watched Ondevilla grow as an artist and a person, marveling at the way he showed up with passion and levity, which wasn’t always the case.

When Ondevilla first returned to City and began studying, he struggled, Hulgin said. The professor recalled a time when Ondevilla, depressed and isolated, shared that he had been sleeping in his car.

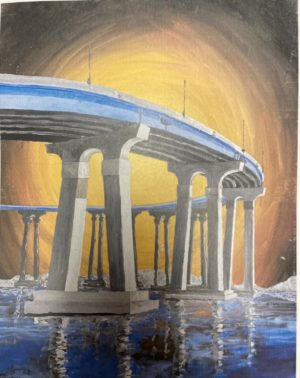

Ondevilla initially translated his pain through his art, his first painting depicting the Coronado Bay Bridge titled “Bridge of Pain,” but he had progressed to expressing love for his family and homeland of the Philippines.

A theme of his latest project is The Philippine High School of the Arts. An homage to the triangular red school building appeared in many of his works and was the main subject of a multi-canvas piece he has been working on for months.

Reflecting on his past, the tragedies and triumphs drive Ondevilla forward, he said, and help him make sense of the world. Hulgin agrees.

“It will never be the same,” Hulgin said, “but I think that making art is one of his ways, probably the only way to survive. And I think it was very therapeutic, like I said before, for him to get back in there and make art.”

Ondevilla, a 2023 City graduate with an associate’s degree in fine art, will be cheered on by his wife and children, he said, who wholeheartedly support his endeavors.

Upon completion of his summer art program in Florence, Italy, his wife will join him and they will visit Lourdes, France to pay homage to his daughter’s namesake, St. Bernadette.

Suicide Lifeline: If you or someone you know may be struggling with suicidal thoughts, you can call or text the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or chat online any time of day or night.