City College professor is giving the dream

Humberto Gurmilan is a former sportscaster who left his job to focus on charity.

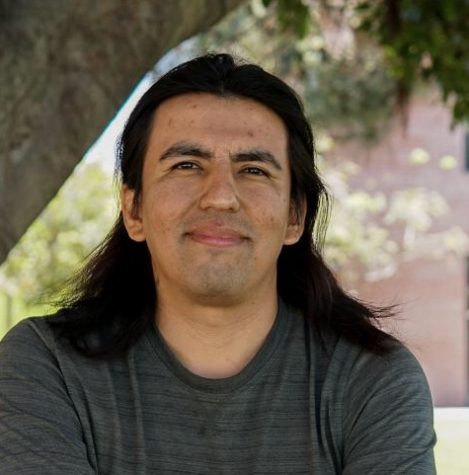

Humberto Gurmilan accepts a donation on behalf of his foundation. Photo by Sonny Garibay

November 20, 2019

Every grownup was once a kid who wanted to be something when they grew up.

Finding a person who lived out their first dream is rare for various reasons.

City College communications professor Humberto Gurmilan did for almost 15 years.

“I knew I wanted to be a sportscaster very early,” Gurmilan said. “Around 10 or 11-years-old I knew that … if I could work for a magazine or a radio station, or a TV station, and cover sports, that was my dream job.”

Born in Chula Vista and raised in Tijuana, a young Gurmilan would invite his friends over to watch the Padres play on TV. They would turn the volume all the way down and do their own play-by-play.

“We were horrible,” Gurmilan said. “We were really bad at it but it was fun.”

Humberto Gurmilan worked as a sports anchor for Telemundo for 14 years.

When it came time for him to attend college, he returned to Chula Vista and enrolled in the Southwestern College Journalism Program. He then transferred to and graduated from SDSU.

As a bilingual journalist, Gurmilan was offered a position as a sports anchor with Telemundo, a position he held until he resigned two years ago.

Sandwiched in-between this story of success, however, is a life-altering accident.

At the age of 15, while surfing near his old home in Mexico, Gurmilan suffered a spinal injury that left him paralyzed from the chest down.

Initially, it appeared that he would not survive.

“When I got to the Red Cross, they told my parents, ‘You better take him to the United States. He’s not gonna make it here,’” Gurmilan said.

He was taken to Scripps Mercy Hospital in Hillcrest. While there, his parents were told by doctors that if he survived, he would be confined to his bed, a detail his parents hid until he was an adult.

Aside from his love of surfing, Gurmilan was a baseball player and was physically active as a teenager. The injury meant huge lifestyle changes for him. Yet, despite some initial depression, he remained optimistic.

“I was blessed with a really strong family with faith (so) when it happened, I knew I was gonna do cool things and have a good life,” Gurmilan said.

The support that he received from friends, family, teachers and coworkers led to an unlikely career in sportscasting.

“Having a disability and being on camera for so long … was an accomplishment itself.” Gurmilan said. “People with disabilities don’t get a lot of opportunities to be in front of the camera. It was a personal accomplishment, but also, showing people that you can do it if you work hard enough and you’re passionate enough.”

Gurmilan’s career has put him behind the microphone at Chargers preseason games, on TV in Spanish speaking households across the San Diego area and face-to-face with local athletes, Olympians and personal heroes.

Grants awarded by the Gurmilan foundation can be used to retrofit vehicles for people with disabilities. Pictured is Gurmilan’s van. Photo by Sonny Garibay

“I was fortunate to be able to do it for 14 years,” he said. “I was really fortunate to be able to meet and to interview some of the people I looked up to.”

Gurmilan remembers his time covering the Padres fondly.

“Sometimes I would use my credential just to watch batting practice. That’s how much I loved it,” he said.

The further he got into his career, the more time he realized that he loved something else as well: giving back. Soon, more of his time was being spent helping others with disabilities, leading to him starting his charity.

Between his demanding job and his desire to give more, something had to give.

When Telemundo was purchased by NBC in 2017, he decided that the time was right to leave the station he helped build and watched grow.

“You have to be 100% in it,” Gurmilan said. “It’s almost like athletes. If you’re an athlete in a sport, you have to be 100% invested in it. At this point that’s the one thing I don’t think I could give because I have too many passions.”

Gurmilan is accustomed to having a strong support system. Whenever he has needed help he has found it, even in unlikely places, such as when reporters from competing stations would help him with his equipment when on assignment.

He is grateful for the help he was given, while understanding that he has been fortunate in the amount of aid he has received. Gurmilan knows what was available to him may not be for others.

“What we’re trying to do is provide those opportunities to other people,” Gurmilan said. “If we can help somebody accomplish their dream, … whatever it is they want to do, that’s the whole soul behind what we’re doing.”

His charity is his focus now. The Gurmilan Foundation aims to assist people living with disabilities to accomplish their goals through scholarships and grants.

Humberto Gurmilan was able to return to the water through adaptive surfing.

Grants can be used for a wide range of things, including retrofitting a vehicle to make it drivable for someone with a disability and covering the cost of travel for athletes with disabilities.

Much of Gurmilan’s time is spent helping others do what they don’t believe is possible, but for 18 years after his accident there was one thing he still didn’t believe he could do.

“When I returned to my everyday life, I never even really thought about surfing again,” Gurmilan said. “I didn’t think, physically, it was possible.”

He would sometimes catch himself daydreaming about waves he once rode.

While working on a documentary about the accident, his friends got the idea for him to return to the spot that he was injured and ride, once again, through adaptive surfing.

Gurmilan said he was terrified at first, not of injuring himself or drowning, but terrified that he would not enjoy the experience.

At first he did not, but after seeing it was possible, he found a group to go with and recommitted himself to the sport, buying new gear and working out until he found joy again.

He now goes surfing every two weeks. In September, he competed in the adaptive surfing portion of the U.S. Open.

In 2020 Gurmilan hopes that the foundation can gain more volunteers and raise even more funds to increase the number of scholarships and grants they award. He also plans to hold multiple adaptive surf camps.

“I don’t know when I’ll stop going forward and doing what I’m doing, with everything I’m trying to accomplish,” he said. “But it’s not anytime soon.”