MAGAZINE: Chicano Park leaders fight for its heritage

City College students in 1970 helped shape the Chicano movement

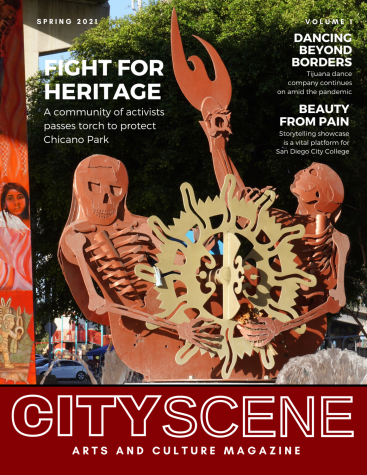

“All the way to the bay” is one of the murals painted in Chicano Park. Photo by Gabriel Schneider

May 24, 2021

Click here to view the debut edition of CityScene magazine.

Click here to view the debut edition of CityScene magazine.

Josie Talamantez remembers sitting in a Chicano Studies class at San Diego City College in April 1970.

At that same time, Mario Solis, another student at City College, had ditched class and noticed construction crews with equipment in the Barrio Logan area.

The land that was once promised to be a park for the community was getting prepped to be a parking lot for a California Highway Patrol station.

Talamantez remembers that Solis came into the classroom, warning the students of the construction workers.

“We all walked outside,” Talamantez said. “We didn’t train to be activists but we, all of a sudden, were aware of the injustices that happened in the community.”

According to the Chicano Park website, several students sounded the alarm, printing flyers and contacting other schools in the surrounding area.

Victor Ochoa, a muralist and student at San Diego State University, said that he saw flyers at the school and went straight to the park.

“Without students the movement really wouldn’t have gotten off more progressively,” Ochoa said.

The students and the community occupied the land for 12 days before they were able to reach an agreement with the city.

During the first evening of the takeover, they established the Chicano Park Steering Committee to become the negotiators and eventually the stewardess of the park, according to Talamantez.

Once bulldozers left the premises, the Cacho family, who were farmers in Otay, brought tractors to Barrio Logan.

“We began tilling and planting the land ourselves,” Talamantez said. “I think that is important to know.”

One year after the takeover of Chicano Park, the murals started to be created. Guillermo Aranda started the first historical murals, according to Talamantez.

Ochoa recalled that he and some of the other muralists visited Mexico to gain inspiration.

We were training to do murals inside the Centro Duality,” Ochoa said. “None of us had been on scaffolds.”

According to Talamantez, the muralists tackled the wall for a couple months before it started to look what it looks like now.

The battle to memorialize the history of the movement and park is far from over.

The next goal for the community is to finish the Chicano Park Museum, which has plans to open at the beginning of 2022.

The San Diego Historical Society identified Chicano Park as a cultural resource 10 years after the creation of the park.

In January 2017, the park was announced as a historic landmark in a press release from the U.S Department of the Interior.

“These 24 new designations depict different threads of the American story that have been told through activism, architecture, music, and religious observance,” said Secretary Sally Jewell, in a 2017 press release.

“Their designation ensures future generations have the ability to learn from the past as we preserve and protect the historic value of these properties and the more than 2,500 other landmarks nationwide.”

Talamantez said, after 51 years since Chicano Park was established, those who participated in the movement are losing their contemporaries due to age and COVID-19.

“We wanted to say to the next generation that you all need to step up,” Talamantez said. “We will be there, we will advise, we will guide, but who knows how much longer we have.”