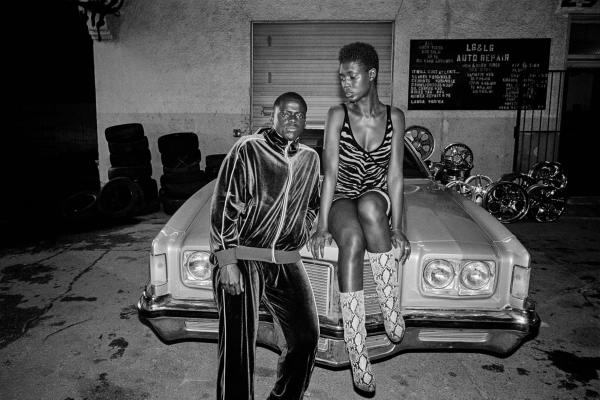

The American Nightmare

A look into the modern black American experience

In a 1967 NBC News interview with Dr. Martin Luther King, roughly three and half years after his famous “I Have Dream” speech on the Washington Monument, King explained to the interviewer that his dream may have been naive. “I must confess that, that dream that I had that day,” King said, “has in many points, turned into a nightmare.” King asserted that while he has not lost optimism, he realizes just how far America has to go before that dream can be fully realized and achieved.

Nearly 50 years has passed since King’s remarks, and there is an argument to be made that America is no closer to fulfilling his dream. It seems that now, instead of black Americans’ mistreatment being dismissed, it is constantly broadcast via news and social media, reminding everyone of our constant strife. This is what it means to be black and American in 2018:

Early in the morning on April 13 of this year, a 14-year-old black boy named Brennan Walker from Rochester Hills, Michigan, had missed the bus to his high school and decided to walk instead. After getting lost, he knocked on the door of a home to ask for directions.The woman inside the home accused Walker of trying to rob her. Moments later, he had to run for his life after her husband emerged with a gun and began shooting at him. Luckily, he was unharmed.

Only two days after that incident, a video showing two young black men being arrested in a Philadelphia Starbucks for sitting as they waited for a friend to arrive went viral. The incident, which occurred because an employee alerted police that the two men were in the cafe without ordering, caused many people to voice outrage and protest Starbucks. The two men were handcuffed and hauled off to jail. Days later Starbucks’ CEO gave a public apology and offered the men $200,000 each, which they both donated to charity.

Shortly after the Starbucks incident on May 12, Donisha Prendergast, granddaughter of reggae legend Bob Marley, found herself and three other friends surrounded by seven cop cars and surveillance by a police helicopter, after their leaving a Southern California Airbnb aroused a neighbor’s suspicion that the group of young black people had robbed the house.

During that same day, Lolade Siyonbola, a black female graduate student at Yale had three cops knock on her door at 1 a.m. because a white graduate student had called the police and reported her for sleeping in the common room area. When the university later stated they felt there was no wrongdoing on the police’s part, but acknowledged some work needs to be done on the relationship between Yale’s campus police and its students.

The black American essayist James Baldwin said, “to be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” To be black and relatively conscious in America is to realize that, despite protesting by black Lives Matter and similar organizations; despite constant think pieces and analytical videos from entertainers like Childish Gambino’s “This is America,” Jay-Z’s “The Story of OJ” and Beyonce’s “Lemonade” all screaming otherwise, America views black people as a monolith. Since the Civil War and Reconstruction era of America, the nation has flooded our society’s consciousness with various media depicting black people as beastly, criminal, roguish and regressive. Early comics depicted black people as animalistic sidekicks to the white and almost universally male protagonist.

It has often bothered me how countless movies and television shows are acclaimed for showcasing the black experience as defined by being oppressed and disenfranchised. Movies such as “12 Years a Slave,” “The Help,” “Glory,” and “Moonlight” depict blackness as constant hardship and brutality.

Throughout my childhood, it was difficult to identify positive images of black people outside of my immediate family. In school, we were taught about colonial kidnappings and enslavement of African people, instead of taught about the mighty civilizations of the African continent. Then we were “educated” on three hundred years of slavery, torture and cruelty.

From those colorful images, my teacher would then jump into how white saviors swooped in and ended slavery. This was the foundation for how our nations views black people, it flooded films, television shows, comics and even commercials. Many black American artists have rebelled against this image, moving the narrative forward to shed light on and expose positive images, like “Marvel’s Black Panther,” in which director Ryan Coogler, a black American filmmaker, shows us a fully-realized vision of an African nation that many have only dreamed about.

For me, to be black in America in 2018 is to be in a constant state of rage, because I feel as though I am not able to progress past the racism that my country has chained me in. Malcolm X said, “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. You pull it all the way out that’s not progress. Progress is healing the wound that the blow made. And they haven’t even pulled the knife out much less heal the wound. They won’t even admit the knife is there.”

This is my experience as a black person, screaming and yelling at America to at least admit there is a wound. Until that happens, we can’t begin the healing process and step out of Martin Luther King’s nightmare to walk toward his dream.

Your donation will support the student journalists of San Diego City College. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, cover the cost of training and travel to conferences, and fund student scholarships. Credit card donations are not tax deductible. Instead, those donations must be made by check. Please contact adviser Nicole Vargas for more information at nvargas@sdccd.edu.